Why Diversity Isn’t Achieving Its Promise

Posted by on

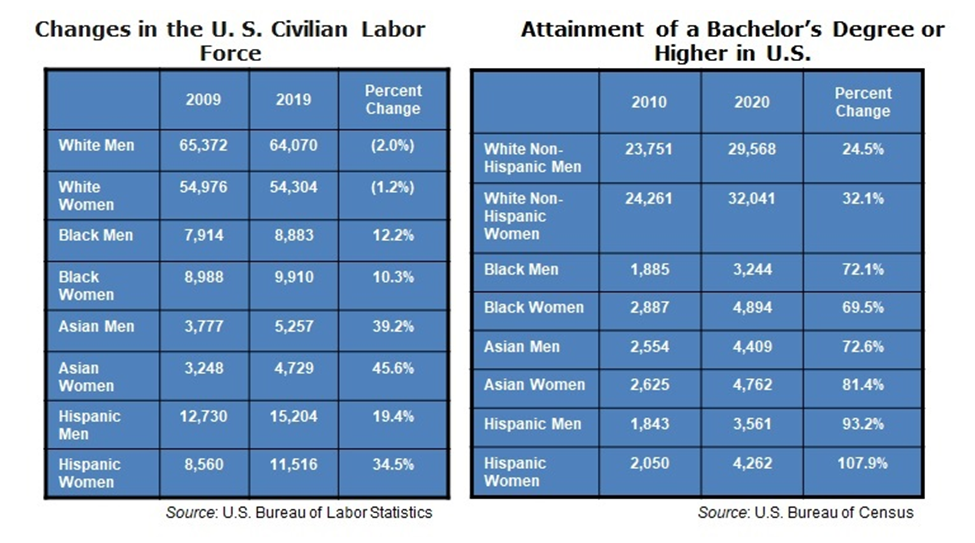

The nation’s institutions are ostensibly making progress toward just and equitable representation of those who have historically been underrepresented. According to U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission data, medium and large institutions are doing a good job of hiring underrepresented people, but those individuals are progressing up the ranks at an anemic pace.  However, when the ten-year trend rates of entry into the civilian labor force and of those obtaining bachelor’s degrees and beyond are examined even that progress is suspect. The percentage of White people entering the labor force is actually declining, while people of color are increasing at double digit rates. People of color are gaining bachelor’s and advanced degrees 2-4 times faster than White people (most senior managers have college degrees). With those rates of change over the last several years, the hiring and advancement of professionals of color should be accelerating at a far more rapid pace, particularly at the supervisory and middle levels.

However, when the ten-year trend rates of entry into the civilian labor force and of those obtaining bachelor’s degrees and beyond are examined even that progress is suspect. The percentage of White people entering the labor force is actually declining, while people of color are increasing at double digit rates. People of color are gaining bachelor’s and advanced degrees 2-4 times faster than White people (most senior managers have college degrees). With those rates of change over the last several years, the hiring and advancement of professionals of color should be accelerating at a far more rapid pace, particularly at the supervisory and middle levels.

Beyond the ugly face of discrimination, this interminably slow or retrogressing progress is rooted in a wide range of causes, including:

- lack of top management commitment

- genuinely committed leaders taking low impact actions

- a goal of inclusion without the knowledge and skillset to achieve it

- the absence of a common language and guidelines for civil conversations about diversity

- not treating diversity as a change process

- failures of implementation

- middle management resistance

- ineffective measurement

- inadequate accountability.

Three additional causes are often overlooked: an over-reliance on best practices, a spotty foundation of empirical evidence, and gaps in the knowledge that leaders need to successfully guide a strategic diversity initiative.

Over-Reliance on Best Practices

Diversity strategy in many organizations is more an agglomeration of bright, shiny best practices than a cogent, integrated strategy. Best practices, even if wrapped in a cloak of strategy, tend to drive organizations toward the tactical. Under pressure to advance rapidly, best practice programs, often artfully designed, are a shortcut to strategy, but are often nothing more than an assemblage of tactics.

A prime business value of diversity is that it differentiates an organization in its talent and product/service markets, those markets in which it competes for diverse talent and customers and clients. Differentiation is a primary source of competitive advantage. By their nature, best practices are copies of the practices of other organizations. And if one organization can copy a best practice, others can too. Adopting the best practices of others creates homogenization not differentiation.

What is a best practice for one organization may not be a very good practice for another organization. Great strategists do not respond to the consequential challenges their organizations face with an assemblage of the best practices of other organizations. They craft the answers in light of the unique people, characteristics, industry contexts, opportunities, and circumstances of their organizations.

Finally, best practices often lack an evidence base. Exactly who is the arbiter of whether a diversity practice is a best practice? Evidence, based on rigorous, systematic, objective evaluation and science is often weak or non-existent.

Spotty Empirical Evidence

Although the empirical foundation of diversity practice is growing, management decisions about diversity initiatives are often based on inadequate or spurious scientific grounds. In addition, diversity practice has made insufficient use of the vast spectrum of exiting interdisciplinary scientific evidence that underpins diversity, including sociology, social psychology, cognitive psychology, neuroscience, behavioral economics, leadership, gender and race studies, education, business strategy, and several other disciplines.

Scientific evidence and the practices it engenders are useless if leaders do not or are unable to apply those competencies to diversity practice.

Gaps in Leadership Competence

In numerous presentations on strategy to senior executive teams, I have found that strategic leaders ask four questions:

- What exactly are diversity, equity, and inclusion (the meaning question)?

- Why should we make diversity a priority (the rationale question)?

- What does our organization need to do to make diversity successful (the strategy question)?

- What do I personally need to do to make diversity successful in my organization (the leadership question)?

To answer the meaning question requires leaders to have forged definitions of diversity, equity, inclusion, belonging, and other concepts central to their diversity initiative for themselves and their organizations. They must also understand and agree upon terms (e.g., Black, African American, African ancestry, or person of color?) to refer to underrepresented populations and establish guidelines for civil dialogue about diversity.

The rationale question compels leaders to understand the eight business cases for diversity and agree on which cases make sense for the unique circumstances of their organization:

- The Talent Case

- The Legal Case

- The Return-on-Investment Case

- The Product/Service Market Case

- The Operations Effectiveness Case

- The Multiplier Effect Case

- The Moral Case

- The Political Case

The strategy question necessitates an understanding of the numerous strategic approaches to strategy, the process of diversity strategy formulation, and the components of diversity strategy implementation, such as how to create equity, inclusion, and sustainable diversity competitive advantage; diversity metrics; accountability; and diversity infrastructure.

The leadership question demands that leaders have a deep understanding of the elements of true commitment to diversity and which elements they will embrace, knowledge of change management and leadership communications, and an appreciation for the requirements of forging a true legacy of diversity for their organizations and themselves.